UPDATE: Nashville General Hospital has since stated its clinicians never agreed to deactivate Black’s implant. The situation is ongoing.

Byron Black’s execution, scheduled for August 5th, hit a snag not only unexpected, but unprecedented as far as I’m aware: Tennessee has been ordered to deactivate his pacemaker before they can kill him.

Black has had a Cardiac Implanted Electrical Device (CIED), which performs both pacemaking and since May 2024. Black was diagnosed with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (also known as congestive heart failure), meaning that the left ventricle of his heart (the part responsible for pumping blood out of the heart and into the body) no longer worked efficiently enough to maintain life. While the device is absolutely essential to maintaining the activities of daily living—such as a man on death row can, anyway—it poses risks to the humaneness of his execution that are difficult to calculate.

Turning Off Byron Black’s Pacemaker Could Prolong His Execution

To understand how lethal injection might interact with Black’s CIED, it’s first essential to understand what the device does in a normal day.

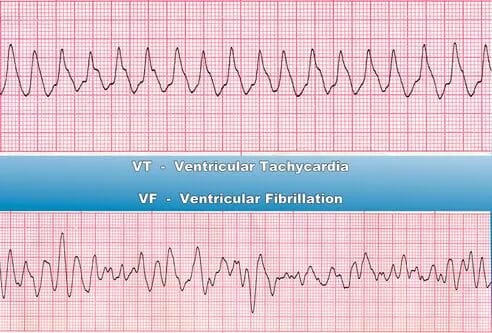

Contrary to the defibrillator use you see on television, defibrillators don’t work on a completely stopped heart. Rather, they fire on a heart that’s in one of two rhythms:

Ventricular tachycardia, in which the left ventricle of the heart fires too quickly to refill with blood

Ventricular fibrillation, in which the left ventricle fires chaotically rather than responding in any organized way to electrical stimuli

Should a CIED or external device (like an AED, or the provider running a cardiac monitor) detect either of these conditions, they will deliver a shock that terminates the rhythm and—hopefully—causes the heart to return to normal function. As you might have guessed, this is how the defibrillator gets its name. When they occur in an awake person—ventricular tachycardia can still support normal function for a short time, and the residual effects of previous heartbeats can support consciousness for up to 30 seconds—they are debilitatingly painful; I’ve seen them knock full-grown adults to the ground.

While there’s evidence that barbiturates like pentobarbital might render Black vulnerable to ventricular fibrillation that would set off the CIED’s defibrillator function, the direct evidence that pentobarbital itself poses this risk is very old, and none of the barbiturate/V-fib studies are human. (Intentionally inducing a human heart dysrhythmia would be challenging, if not impossible, to get past most institutional ethics committees).

The real concern is the device’s pacing function. When a heart falls below a threshold that can sustain life (usually fewer than 60 beats per minute), a pacemaker responds by simulating the electrical pulses that cause heart contractions. This, by contrast, is exactly what lethal injection is designed to do: while pentobarbital doesn’t directly activate the parasympathetic nervous system (which lowers the pulse), the depression of the nervous system accomplishes the same effect. If Black has not been rendered insensate (not simply unconscious but impervious to feeling, a level of anesthesia that states successfully fought ever having to ensure) by the injection of pentobarbital, the device will keep his heart humming as he experiences the feeling of drowning in his own lungs (a condition caused by pulmonary edema, to which Black’s heart failure renders him predisposed already). Continually pacing him in the place of organic heart activity might also trigger one of the dysrhythmias mentioned above, which it would attempt to correct via shocks.

There is, of course, a third risk: Black’s pacemaker is designed to keep him alive, and there’s still something to live for. According to his clemency petition, “every single expert who has actually evaluated Mr. Black has concluded that he is intellectually disabled;” he only remains on death row because a 2021 change to Tennessee’s procedure for evaluating intellectual disability claims came after he raised his own. While the court didn’t consider these claims, it noted that deactivating the pacemaker too quickly might inadvertently kill Black before the governor had a chance to spare him.

Who Will Turn Off Byron Black’s Pacemaker?

Modern implanted cardiac devices maintain a “read switch“ in case they are incorrectly reading heart rhythms or patients need sedation for a procedure. While a magnet can, in a pinch, activate this read switch, only a full deprogramming can ensure the pacemaker won’t be functioning during the execution. (The process for deprogramming a pacemaker is explained here.) While either would require a qualified technician, a deprogramming requires advanced equipment a state is unlikely to get its hands on quickly amid the continued resistance of the medical establishment.

While the judge’s original order required that the pacemaker be deactivated “shortly before or at the point of the lethal injection” in order to maximize the potential for a stay of execution, he clarified that this was not intended to delay the execution. After Black’s physicians told the state they were unwilling to attend the execution in order to deactivate his pacemaker, the judge allowed the procedure to take place at a Nashville hospital the morning of the execution. Merely tinkering with place and time, however, doesn’t alleviate the ethical concerns involved.

For a long time, physicians participating in executions have danced along an ethical tightrope. Forbidden by boards and discouraged by the American Medical Association from actively participating, they’ve exploited supposed loopholes like only witnessing the execution, or only pronouncing the death of the person executed, to get around the notion of “participation.” By contrast, lethal injection’s pharmacological godfather, Jay Chapman, said that since none of this actually was medicine, there was no ethical conflict with participation.

What Tennessee is asking for falls way too far into “second, do some harm“ territory for any of these arguments to cover it. Deactivating a pacemaker is inescapably a medical procedure, and the stated purpose here is—eventually—to kill the patient. Whoever decides to help Tennessee kill Byron Black won’t even have the slender reed of medical-ethical cover that death-dealing healthcare providers have traditionally relied on.

1 Certain civil matters in Tennessee, like this one, are resolved in “Courts of Chancery.“ The judges presiding over them are referred to as “chancellors;“ I have used the equivalent and more familiar term “judge“ here.

2 The midlevels, nurses, EMS personnel, and pharmacists participating in executions face the same condemnation from professional associations, but they’re less powerful.